The New Year means different things to different people, but for many of us it means being grateful that we have another 12 months before we have to worry about budgets.

This post is about a different kind of budgeting: budgeting our emotional energy. Emotional energy is the cash we need to purchase work from our bodies and minds, that is, it’s the key to motivation.

Unfortunately, robots will not be learning how to learn languages any time soon.

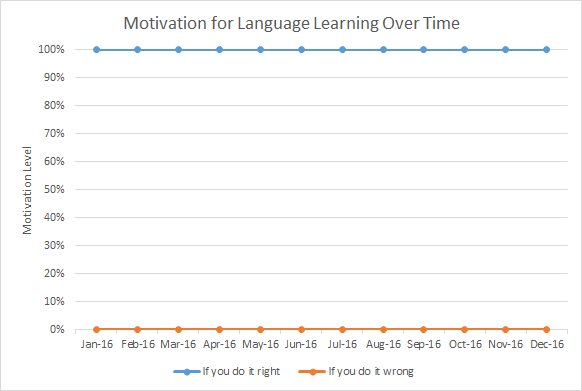

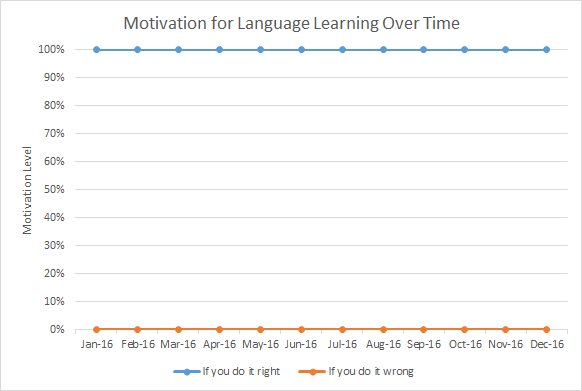

Language learning is a slog, and we need to make sure that we have the emotional energy to do it. Now wouldn’t it be nice if we could just learn the right way to do it?

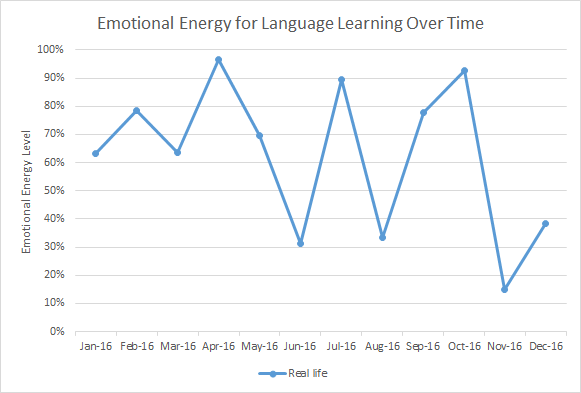

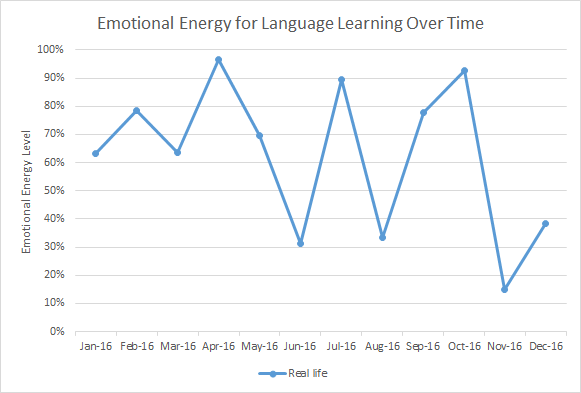

The reality is that life happens. Our emotional energy ends up looking more like this:

Since we’re living in the real world, we need to plan for variation in our emotional energy. When you’ve got energy and are motivated, you’re golden. The problem comes when we’re feeling down. Here are some tips to keep your energy level high.

Make your language time enjoyable

At the risk of losing my position, I make this confession: I don’t particularly like language lessons. When it’s time for my language lessons, I usually pour myself a cup of tea, put my feet up on my desk, and read a Dari book. That is how I relax. That’s the kind of learning I enjoy.

If you’re more extroverted, spending time getting to know people might be more enjoyable. Know thyself. If thee dost not know thyself well, thee might want to take our Learner Profile.

“Enjoyable” might mean “productive” for you. My preferred way to spend time with a teacher is in working on a real-world task, such as preparing for a talk, or revising something I’ve written.

Think about your personality and what feels good, and make your language study time reflect that.

Plan for success

Keeping your emotional energy high will mean planning positive experiences—times when you succeed in using your language. For some people this will mean taking a walk in the bazaar or visiting in a private home. Receiving positive feedback in your language is encouraging, and Afghans love to encourage people who speak their languages. It might mean doing a work-related task in Dari rather than English, and enjoying that sense of accomplishment.

The key here is to plan positive interactions in your week, so that you can enjoy the sense of having made progress.

Celebrate success

When you have a successful interaction, focus on that. The discouraging interactions are bound to come, so we need to pay special attention to when things go well. Every three months or so I can pull off a joke in Dari. I replay it in my head for weeks afterward. (That may be an extreme example.)

The converse is to downplay your failures. It’s good to learn from our mistakes when we can, and even better to be able to laugh about them. Your reaction to failure is probably largely a function of your emotional energy. At the same time, perhaps there are patterns of negative thoughts that you need to break out of.